The Construction of Space Shuttle Launch Complex 39-B

A very personal and technical written and photographic history, by James MacLaren.

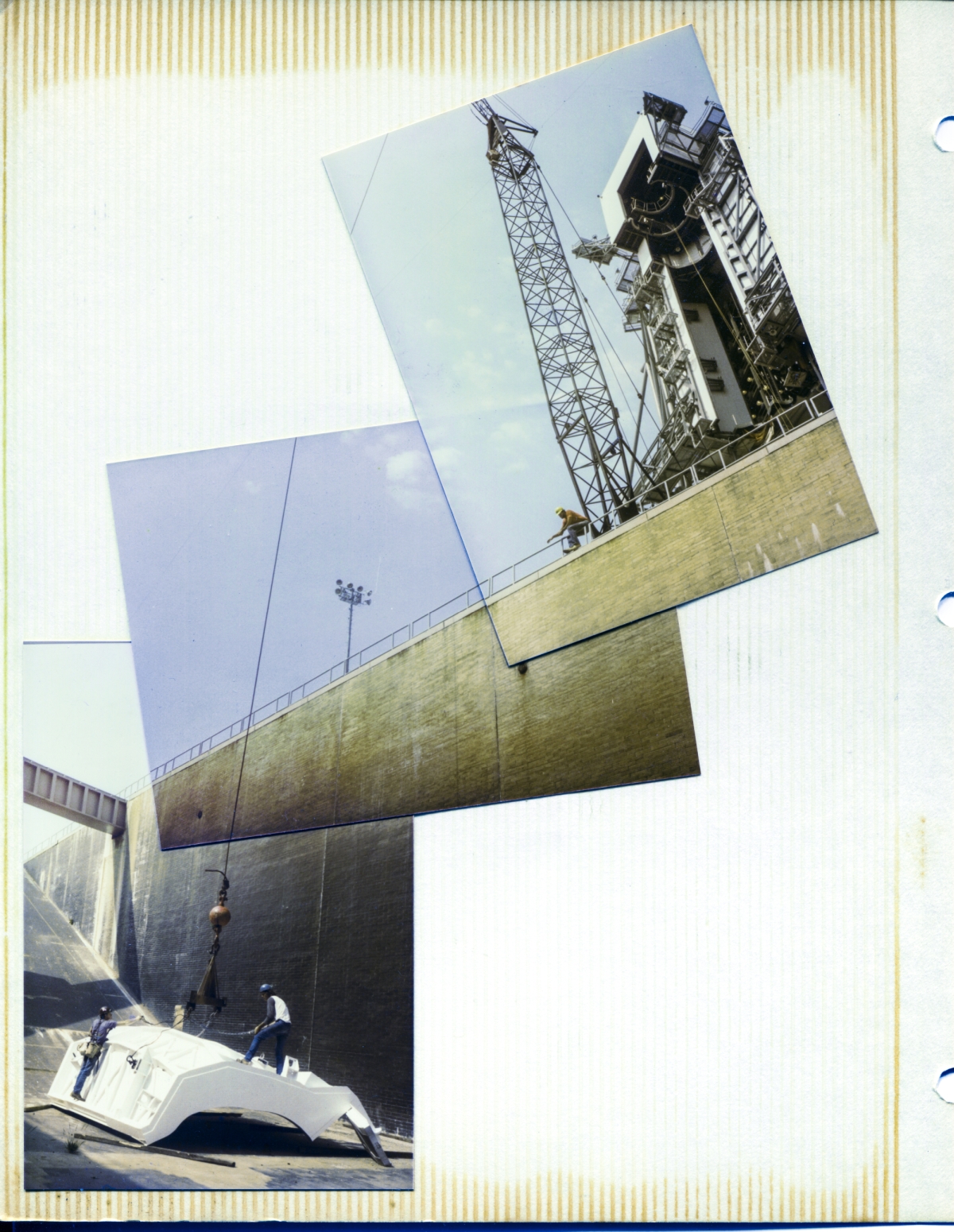

Page 51: A Colossal Blocky Presence, with Fire Bricks and Pod Covers.

| Pad B Stories - Table of Contents |

Another one of my favorites.

The aesthetic alone, makes this one a winner, but there's so much more than that.

However, let us not leave the aesthetics behind just yet, shall we?

You are hemmed in by a great brick wall, and an equally great (and steep) ramp, looming high above you.

Beyond, looming vastly higher yet, a great construct glowers down upon your unworthy self, looking almost Egyptian in its colossal blocky presence.

Whatever fearsome gods that were paid homage to in a place like this must have been very potent, very powerful, very oppressive.

On top of the wall, dwarfed by all before and behind him, an overseer keeps a watchful eye upon his minions, laboring down at ground level.

They stand upon an inscrutable white object, something that would not look particularly out of place in a painting by Salvador Dali, laying procumbent, which has allowed itself to be tied up, to be readied, but for what?

Who are these people?

What is their business?

And what is this place?

The image is mute, and offers nothing more.

Yeah, this is definitely one of my favorites.

Here it is again, this time in full resolution, and for whatever reasons, this particular set of three overlapping photographic prints, taken with a small hand-held camera having no specialty lens, using commonly-available 35mm ASA 400 Kodak Kodachrome film which was developed at a neighborhood business which treated that film in no special way, came out astoundingly good and contains an even more astounding level of well-delineated detail, and we will be getting into that detail, but not right this moment, ok?

Of all the images I managed to capture while working out there on Pad B, this one comes closest to capturing the overwhelming scale of things.

Mind you, it does not capture that scale...

...but it begins to at least hint at it...

...in a very limited and in a very inadequate way...

...but the feel of things is limned faintly...

...out on the far edges of sensation...

And that scale was vast.

Beyond imagining.

And to think of what kilned in seconds, the whole expanse of those refractory bricks which line the floor and walls of the Flame Trench...

...black...

Partially melting their exposed surfaces in wide areas...

No.

The human mind cannot go there.

Even when you're standing right there, with the soles of your boots on it.

Your mind really wants that black to be some kind of grime.

Really wants to be assured that what it sees is correctly understood.

The shading of it. The tones of it. The coloring of it. It is all exactly perfect in its mimicry of a sooty deposit left by some sort of fire somehow.

And even though you already know...

Even though you have already done this before...

...more than once...

...you find yourself walking over to the foot of that looming wall or simply stooping over where you stand, and you rub your fingers across it.

And your mind wants there to be a black residue to come away on your fingertips.

And it doesn't.

And you do it again, pressing harder this time, wetting the tips of your fingers before you do so, trying to cause this obvious sooty residue to come away on them...

...but it refuses you.

Smooth.

Clean.

There is no residue.

And your mind absorbs this counterintuitive news...

Only partially...

And you look closely at it...

And you consider it...

And you consider what you're standing on and surrounded by...

It is neither ceramic nor obsidian...

But it lies somewhere in between them...

And the sort of fury which could metamorphose the surface expanse of gritty yellow firebricks all around you into such a thing...

And your human mind cannot go there.

Even when you're standing right there, with the soles of your boots on it.

This effect, this fury hurled at the firebricks which lined the Flame Trench like an onslaught from a host of enraged gods, metamorphosing them as it did so, is hard to properly grasp, even after it has been fully explicated, and you have been made sensibly aware of it, and you therefore know about it.

But.

Mirable dictu, our photograph at the top of this page was taken, by sheerest dumb luck, at the right time, from the right vantage point, with the right lighting, to let you actually see the effect.

But before we point it out for you, knowledge being power, let's get a closer look at exactly how these firebricks were put together to make up the exposed surfaces of the Flame Trench walls and floor.

Firebricks can be googled easily enough, and I'm not going to delve into the materials they're made from, or how any of that stuff works, ok? It's pretty basic technology and infrastructure. Been around for a long time. Well-trodden road. We'll leave that as an exercise for the student.

I will give you a look at a firebrick, though, so you can see how they're ruler-straight perfectly-flat on all sides, with nice hard edges, all the way around.

Like this.

Nothing too fancy there about the basic nature of the brick itself, and about the only thing to take note of is that when these things are all fitted together in the Flame Trench, it becomes a close fit, and has no sensible gap between individual bricks like you see in regular "brick and mortar" construction, because there is no mortar, ok?

And this obtains everywhere except for where the bricks meet the expansion joints in the concrete beneath them along the bottom of the Flame Trench, at which points they specified a ⅜" gap filled with "compressible fireproof filler", between those particular bricks abutting the gap, with that gap in the bricks offset from the expansion joint by ¾", and behind them where the bricks meet the expansion joints in the concrete along the vertical extent of the Trench Walls, where they specified the ends of the bricks be step-cut, with an offset of ½" to either side of the expansion joint, separated by ⅜" of "compressible fireproof filler" on either side of the expansion joint across the depth of the brick, and they called for this on A-316, directing our attention to A-317 for the detail itself.

We never construct things with joints or other potential zones of weakness in this, which will line up point-for-point with another joint or potential zone of weakness in that, unless it is our specific intent to guide and control a failure that we probably are not going to be able to avoid, otherwise. So we offset this stuff, just a little bit, no more than is really necessary to prevent forces from all concentrating together in the same exact place, as a matter of standard practice, ok? And we'll be getting to see a line of that "compressible fireproof filler" for ourselves here in just a bit, ok?

And without mortar, the bricks need to be held in place somehow, and on the Trench Floor they simply laid them down over epoxy cement, and along the walls... it gets surprisingly complicated.

So. Except for where the concrete beneath them had an expansion joint, it was brick-on-brick, with a nice even surface all the way across, from one end to the other, no gaps, no sealer, no filler, and it makes for a very smooth surface, so long as what the bricks are attached to, what they're being held up with, is also nice and smooth, and when they originally built the Flame Trench, back in the Apollo Program Days, they very definitely spec'd out a smooth concrete substrate upon which to place their firebricks.

All well and good.

Here's the original Apollo Pad B architectural drawing, A-317, without comment or mark-up, telling us how to put our firebricks together, including the details for what we're supposed to do when we get to an expansion joint in the underlying concrete that I just mentioned.

And these are specialty firebricks, and there are a few particulars about them which you may not encounter with the firebricks you might come upon elsewhere, so we're going to be giving that a look, too. For one thing, along the Flame Trench Walls, they were keyed, which is just a confusing word to tell you they had matched grooves and projections which snug-fit together to keep the so-joined bricks from moving around in relation to each other. The keys kept the bricks in place, where they could not get loose or get pulled out from where they had been installed.

This is the best picture I've been able to find of a keyed brick, and this image is NOT one of the bricks used at the Pads, and has a completely different overall shape and set of dimensions, but the key is more or less identical, and for that reason, it is usefully instructive.

And those old Apollo drawings are harder to read. Less user-friendly. So I'll mark A-317 up some for you, to help you see what's going on with those firebricks, before we take our very close look at 'em in the photograph at the top of this page, to see how they evidence the the Hadean forces which they have endured.

So here's A-317 again, marked-up this time, letting you see the details of the plain-shaped bricks on the Flame Trench Floor and the keyed bricks on the Walls, along with the clever dovetail anchors set into special notches which were cut into some, but not all, of the bricks, which they used to hold those keyed bricks in place in a way that kept it all solidly-fastened to the concrete beneath it, and yet provided for that ever-so-smooth mortarless surface with the bricks butted together into a single smooth plane that the gave the exhaust from the Saturn V, and of course later on the Space Shuttle, nothing to get hold of, to pluck, to pull, to render apart, that which it was so ferociously in direct contact with.

I've got a feeling those bricks turned out to be surprisingly expensive to furnish and install. Stuff like this is fussy, and tends to chew up an outrageous amount of labor hours on what you might otherwise consider to be a job that is just about as basic and well-understood as it gets. I can just hear somebody whining about it somewhere with an incredulous voice tone, "They're just laying bricks. How hard can it be?"

Plenty hard, actually.

Hope you budgeted enough time and money for this one. You're gonna need it.

So. Now we know how the bricks got installed. Brick against smooth-face sharp-edged brick, no mortar. Let's go from there to the subtleties of how that allows us to extract good evidence of the ferocious conditions which they have endured in the past. Let us return to my previous remark where I said, "Mirable dictu, our photograph at the top of this page was taken, by sheerest dumb luck, at the right time, from the right vantage point, with the right lighting, to let you actually see the effect."

I've cropped in on things, but not too far, to let you see where you are, and to let you see the shadow of the Rail Beam which spans the Flame Trench, and which carries the RSS across it, cast against the Flame Trench Wall (which runs precisely north-south), and that shadow is slanting downward at a pretty steep angle, telling us the sun was pretty high in the sky when I took this photograph. Additionally, the sun was nearly parallel with the Flame Trench Wall, causing the illumination of the bricks in that Wall to be very oblique, slanting down and across the bricks, from above and to the left.

If the bricks were unaltered, this strongly-oblique illumination angle would not be showing us much at all. Flat surface of bricks, and nothing more, really.

But look close, and you can see that each and every brick is casting, to one degree or another, a slight, but very distinct, shadow along its lower margin and its right-hand margin, too.

These shadows are complimented precisely and uniformly, by a lightening that runs along the top edge of every brick, and along the left side of every brick, too.

And then, along the area of the brick's surface, there is an additional oblique-lighting effect where that surface appears (and is) slightly domed in aspect. Each brick, to a greater or lesser degree, gives clear evidence of a sort of bulge, a sort of puffy appearance.

And it's not a strong effect, and my photograph can only take us so far, and no farther, but it's very definitely a real effect, and it tells us, loud and clear, that along the margins of each and every brick, over a period of time lasting not many seconds at all, during liftoff, the concentrated forces of hell itself were raging transversely across those margins, which, to however imperceptibly slight a degree, were that much more exposed to them, and which, as a result, were more transformed by them, and in the end, that smooth even surface of yellow firebricks was rendered into a near-ceramic, and eroded on the margins of every brick as that occurred.

Following their original installation on the surface of the Flame Trench Wall, these bricks have remained utterly untouched by anything.

Except for those moments, those few seconds, when the flames unleashed by a Saturn V or a Saturn 1B engulfed them.

And this only happened one time with a Saturn V (Apollo 10), and an additional four times with a Saturn 1B (all three crewed Skylab launches plus the single Apollo-Soyuz launch), and you can find the footage for yourself, and work out the total amount of seconds these bricks were exposed to such a thing, and yet...

Slightly domed. Slick-black near-ceramic.

In seconds!

The human mind cannot go to a place such as this, and so we shall quit trying, and depart.

Ok, what's going on here? What are they doing, down there in the bottom of the Flame Trench?

OMS Pods Heated Purge Covers. It's coming, get ready for it... but not quite just yet.

We first met them back when we were Tracking the Steel, on Page 3 - Orbiter Mold Line Grating Panels 135.

They're unhooking the wire ropes of a four-legged lifting sling from the Left OMS Pod Heated Purge Cover. Above the Cover, the sling attaches, two legs on each end, to the spreader bar, which itself is attached to the crane hook, with a lifting shackle, and the high-resolution version of our photograph up at the top of this page is sufficiently-detailed as to give us what might be our best look in all of my photographs, at a complete assembled set of the sort of lifting gear which you might find down at the business end of a whip line, which was in common use at the time.

This is just one single example, and there's zillions of different ways of putting this kind of stuff together, from no end of different kinds of stuff which makes it up, that can be used to assemble it, all of which are multivariously-dependent on what's getting lifted, where it's getting lifted from, where it's getting lifted to, how much it weighs, what kind of overall shape and center-of-gravity it has, what's picking it up, what's laying around on hand at the job site to use that will get it done safely and efficiently in least amount of time and expense, and no end of other imponderables.

Shackles of one sort or another hold all of the elements together in a manner which allows for rapid disassembly and reassembly of those individual elements necessary for making up the gear on any given occasion, to account for the very different things which might be getting lifted, and the very different circumstances which might be encountered in those lifts.

The headache ball (nobody ever called it an "overhaul ball") in this image can be seen for the large and very heavy thing that it really is, and this is a bit unusual, because in most images you encounter with a crane lifting something, the headache ball always seems to look small and non-threatening. They come in different sizes, some of which might appear to be "small", but all of them are substantial items, and must be treated with the full respect which they are always due.

In our image, overhanging a five-story drop, Ivey Steel's general foreman Rink Chiles is watching the work down in the bottom of the Flame Trench closely, using his right hand to give signals to the crane operator behind him, unseeable in this image. The crane operator, needless to say, is completely unable to see any of what's going on, down at the end of the whip line, and all parties involved possess a level of competence and trustworthiness that allows this sort of work to be done on a regular and reliable basis. None of it is easy. None of it is without risk. But everyone involved trusts and relies upon everyone else, and the work gets done.

Down on the Pod Cover, our right-hand ironworker, standing up on top of it, is Rink's brother, Reuben. Our left-hand ironworker, alas, must remain unidentified.

Union Ironworkers very commonly came in family groups. Siblings, parents, children, and more distant relations of all types, all working out of the Local 808 union hall, sometimes on the same job, oftentimes not, ever-changing, ever dependent upon the vagaries of contracts, budgets, schedules, and no end of other considerations which affected the daily ebb and flow of human manpower, here, there, everywhere.

Union Ironworking is a remarkably-small World, and the same faces, the same families, would be encountered over and over again, year after year, job after job, and everybody knew everybody else, and there were no job-site secrets. Everybody knew everything about everybody else. The good, the so-so, and the bad.

Arrangements and accommodations for individuals, based on their well-known track records in this tightly-knit world, were unspeakingly and unwaveringly adhered to at all times.

Everyone had their places in the wider picture, everyone had their own viewpoint on things from the inside, and whether silky-smooth or with occasional rough friction between parties, the work got done.

Once someone had successfully completed their apprenticeship, made the cut (and most assuredly not everyone was able to do so), and made the transition to journeyman, then that was that, like them or no, if they got it done.

Ironworking, above all else, is a team sport, and you must be a good team player. It is also, far too often, a life and death proposition, and there was zero tolerance for anything that might constitute any kind of real risk.

There were competency and trustworthiness floors beneath which people were not so much as tolerated up on high steel. Were not permitted mere entry into the world. You do NOT put people at risk (which very much includes putting yourself at risk, because it may cause them to be put at risk, working to extricate you from whatever dire situation you might have foolishly or incompetently gotten yourself into), up on the iron, for any reason, with any justification, at any time, in any way. The web of connections was a tight one, and no weak links were tolerated in any of the chains that bound it all together.

In the 1980's ironworking was an overwhelmingly male profession, and those few women who learned the trade and entered The World, had to deal with much from too-many unpleasantly-misogynist parties to count. And as a result, none of them brooked any shit from any one. Fierce independence and toughness were demanded of them at all times, and they achieved regard and respect up on the iron, just like all of the men had to, but it was never an easy road for any of them.

Meanwhile, back at the Pod Cover, Reuben is standing on it in a way that may or may not be particularly beneficial for its thin panels of aluminum skin which filled the spaces between its aluminum framing members, but Rink does not seem to mind, and is happy to let his brother continue with working the rigging, by whatever means seem best, and in the end, I recall no issue with the structural integrity of this thing.

That said, the Pod Covers were surprisingly flimsy constructs, made up of a very large number of aluminum structural shapes, skinned over with some pretty thin aluminum plate, all of which was welded together, and yes I'm sure these were a certified nightmare to put together in the shop, and if memory serves, that shop was SMCI (Specialty Maintenance & Construction Incorporated, and those people were good with this kind of stuff), over in Lakeland, Florida, and as anybody who has had to work with it can well attest, welding aluminum can be a real bitch because of the unpleasant way it reacts to having that kind of concentrated heat introduced into it in small areas. Without particular care being taken during the process (and, too often, even with particular care being taken), aluminum welds will want to crack if you so much as look at them crooked, and the overall piece being fabricated will also want to warp, and sometimes warp badly, if you're not additionally careful. Lotta pre and post heat-treatment with aluminum weldments. Lotta weld inspection with aluminum weldments. Lotta QC inspections with aluminum weldments.

Engineers love the stuff, because it's fairly cheap (material cost, anyway), lightweight, and strong enough (for the most part, anyway, and it will hold itself together well enough, but it should never be trusted too very far with holding you together), but everybody else hates it, and not just because of fabrication issues, either.

The stuff causes problems out in the field, where it meets the iron, even when it's fabricated perfectly.

More to come, on this. Much more.

But not right now, ok?

In the far top right of our panorama image, the face of the RSS glowers down on all before it and below it, and we're looking up at it from an angle well beneath the Pad Deck, five stories up above us, which you will find nowhere else (my images, or anybody else's images, either), and for that reason alone, it is worth a bit of extra consideration, above and beyond what I mentioned at the beginning of this page regarding the aesthetic of the thing.

From this angle, some of the earliest beginnings of what Ivey Steel did to the RSS are visible, so let's see if we can make a little sense of it from out present vantage point.

Our area of interest is down at, and in the vicinity of, the PCR Main Floor, elevation 135'-7", and here it is cropped-in for you, to let you see where we are.

And here it is again, labeled, pointing out the precise location of the ongoing work on the Orbiter Mold Line at elevation 135'-7", and the as-yet undisturbed PBK and Contingency Platforms, which, very soon, will be extensively reworked.

This photograph, by sheerest accidental good luck, managed to catch the work on the Orbiter Mold Line roughly midway through the process of removing the existing perimeter steel along with its support framing, prior to the installation of new support framing and perimeter steel. My guess is that the difference of a single day, either earlier or later, would not have shown this demo work as you see it, only partially completed. Torchwork goes fast, and the business of tearing this stuff out was done in the blink of an eye.

We are exceedingly lucky to be given this chance to see it as it happened.

Soon enough, all of what you see labeled will be gone forever, utterly altered in appearance and function.

Soon enough after that, the entire visible face of the RSS will get near-totally blocked from view, never to be seen again, by what was to come.

The RSS was more process than it was thing, and as it moved forward through time, it changed, and it changed drastically in places.

Let us now return to it. Let us go back up there, once again. There is much being done up there. There is much to see up there.

Return to 16streets.comACRONYMS LOOK-UP PAGEContact Email Link |